In the delivery and adoption of new technologies to smallholder farmers, the role of smaller regional seed companies should not be overlooked.

By Ido Verhagen, Executive Director Access to Seeds Index

When Chris Anderson introduced his groundbreaking Theory of the Long Tail in Wired Magazine (2004), he used this to describe the new marketplace that was emerging as a result of falling costs of production and distribution. He outlined how the economy was shifting away from a focus on a relatively small number of mainstream products and markets at the head of the demand curve towards a huge number of niches in the tail.

The same metaphor can inspire to describe the structure of the seed industry: a small group of big global players and a long tail of smaller regional, national and niche players. For obvious reasons, it is this first group of market leaders that receive the most attention – even more so at times when three proposed mega-deals are set to further reduce the number of companies responsible for a significant part of the world’s commercial seed sales.

Still, the relevance of the companies in the long tail of the seed industry should not be overlooked. For instance, in the delivery and adoption of new traits and seed varieties to smallholder farmers collectively dominating the regions that are facing food and nutrition security challenges, these companies play a key role.

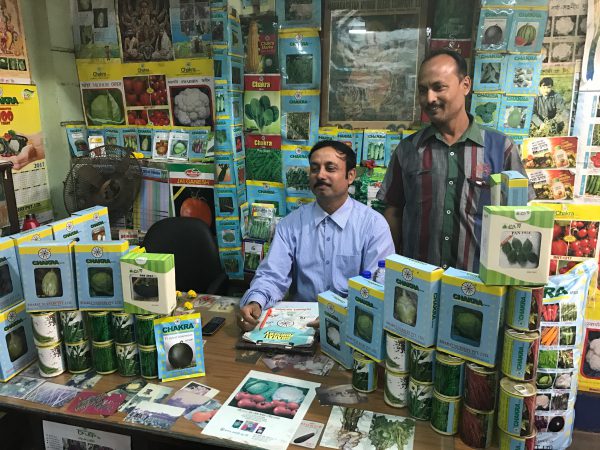

Chakra Seed, a leading regional seed company in West Bengal, is one such example. Through its fine-grained network of dealers and retailers all over the Eastern Indian state, and, with the support of lead farmers demonstrating the use of newly developed seed varieties in remote communities, it has successfully introduced hybrid vegetable seed throughout the region.

The first Regional Access to Seeds Index for Eastern Africa highlighted the important role that seed companies originating in the region play to increase access to quality seeds for smallholder farmers in East Africa. Many outcompeted the global companies in this benchmark through leveraging their local presence. On several aspects, such as reaching remote villages, collaborating with local farmer communities to inform their R&D decisions or capacity building activities, they can take it a step further than their global peers.

Although some regional companies have their own breeding programs, they are often not the developers of new technologies and germplasm for many crops: they in-license or buy the technologies from public research institutes or bigger seed companies for further development, testing it for local suitability and introduction to the market. Through their knowledge of the local market and a strong customer base, they know what farmers and customers want in a certain region, and put the right seed products in the right place.

One company successfully following this model is the Kenyan East African Seed Co. with distribution channels all over Eastern Africa. At its breeding station near Nairobi, it uses varieties for maize, rice and beans coming from public research institutes to test and improve their suitability for the region. Although it also has a large portfolio of vegetable seed, it does not have its own breeding program for vegetables. For this, it partners with global vegetable seed companies.

Interestingly, when the UN High Level Panel presented advice that resulted in the Sustainable Development Goals Agenda, it also described how the private sector could partner on this agenda to drive sustainable and inclusive growth. The panel envisioned a central role for small and medium-sized regional firms reaching local customers and communities with tailored products, and larger global firms using their expertise and global reach to link regions and make technologies widely available through local partnerships. The interwoven nature of the seed industry, largely made up of collaborations and cross-licensing between global and regional players, provides a great example.

To create a better understanding of the role regional seed companies are playing and identify who they are, what their specific strengths are, and what their current presence and portfolio looks like, the Access to Seeds Index will expand its regional scope towards South Asia and West Africa in a premier edition currently under development.

For providing access to new technologies to smallholder farmers, the interwoven web of licensing and collaborative structures within the seed industry is a crucial asset but also requires an enabling environment supported by coordinated and effective public sector efforts.

In reflecting on the impact of concentration in the top of the seed, and when evolving and locally implementing global arrangements in the handling of genetic resources and intellectual property, it is essential to ensure that the long tail of the seed industry continues to be enabled to play its critical part.

This blog was published on the Crop Science Blog page of Bayer Cropscience